The Catholic Church holds that during the Eucharist, the bread and wine consecrated at Mass become the true Body and Blood of Jesus Christ through the doctrine of transubstantiation, a mystery rooted in Scripture (e.g., John 6:53-56) and formalized at the Council of Trent (1545-1563). While this transformation is a daily occurrence in Catholic liturgy, certain extraordinary events—known as Eucharistic miracles—have provided tangible signs of this belief. These miracles, investigated with rigor by Church authorities, are deemed worthy of belief but not obligatory for Catholic faith. Let us have a look at some of the most significant and officially recognized Eucharistic miracles, spanning from the early Middle Ages to the modern era.

Lanciano, Italy (c. 750)

Considered the first recorded Eucharistic miracle, this event took place in the 8th century in Lanciano, a small town in the Abruzzo region of Italy. A Basilian monk, struggling with doubts about the Real Presence, was celebrating Mass when, during the consecration, the Host transformed into visible human flesh, and the wine turned into five globules of blood. Overwhelmed, the monk and his community preserved these relics in a monstrance. The flesh, identified as myocardial (heart) tissue, and the blood, type AB, have remained incorrupt for over 1,200 years. In 1971, Professor Odoardo Linoli, a respected anatomist, conducted a scientific study commissioned by the Church, confirming the tissue’s human origin, its lack of preservatives, and its consistency with fresh heart muscle. The relics are housed in the Church of San Francesco, drawing pilgrims annually, and this miracle significantly influenced Eucharistic theology.

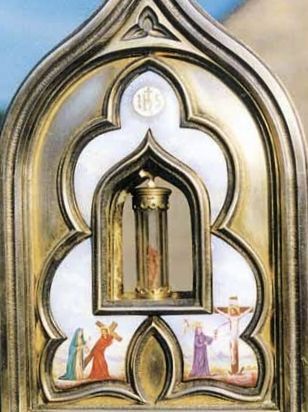

Bolsena-Orvieto, Italy (1263)

This miracle occurred in the town of Bolsena, involving a Bohemian priest named Peter of Prague, who harbored doubts about transubstantiation while on a pilgrimage to Rome. During Mass at the Church of Santa Cristina, the Host he consecrated began to bleed profusely onto the corporal (a linen cloth used in the liturgy). The bloodstains formed a pattern, and the event was reported to Pope Urban IV, who was in nearby Orvieto. The Pope ordered an investigation, and after confirming its authenticity, he instituted the Feast of Corpus Christi in 1264 to honor the Eucharist. St. Thomas Aquinas, at the Pope’s request, composed the liturgy and hymns for the feast. The bloodstained corporal is now enshrined in the Cathedral of Orvieto, where it remains a focal point of devotion and study.

Santarém, Portugal (c. 1247)

In the small Portuguese town of Santarém, a woman facing marital strife sought a sorceress’s help to restore her husband’s love, offering a consecrated Host as payment. During Mass, she took the Host, wrapped it in a veil, and hid it at home, where it began to bleed miraculously. Terrified and repentant, she confessed to her priest, who returned the Host to the Church of St. Stephen (now the Church of the Holy Miracle). The bleeding Host, preserved in a wax container, continues to exude a reddish substance, analyzed in 1997 by the World Health Organization as human blood of type AB. The miracle, approved by local Church authorities, led to the site’s recognition as a pilgrimage destination.

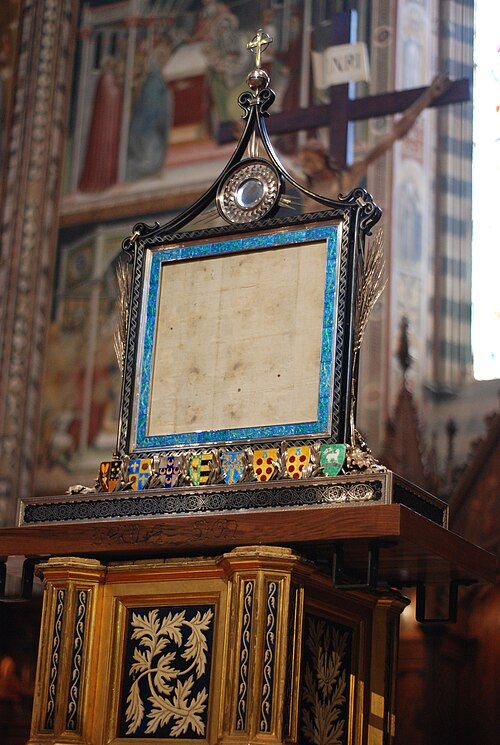

Siena, Italy (1730, with origins in 14th Century)

The Siena miracle traces back to a theft in the 14th century, when robbers stole consecrated Hosts from the Church of St. Francis. The Hosts were later found in an offering box, covered in dirt and presumed ruined. Remarkably, they showed no signs of decay over decades, defying natural processes. In 1730, Church officials documented their preservation, and they are now venerated in the Basilica of St. Francis. This event underscores the theme of divine protection over the Eucharist, with periodic examinations confirming their intact state.

Amsterdam, Netherlands (1345)

In Amsterdam, a man too ill to retain the Host after Communion vomited it. Following the priest’s advice, his family cast it into a fire to dispose of it, but the Host emerged unscathed the next morning. This miracle, investigated by local Church authorities, was interpreted as a sign of the Eucharist’s sacred inviolability. The event is commemorated in Dutch Catholic tradition, though the original Host was lost over time.

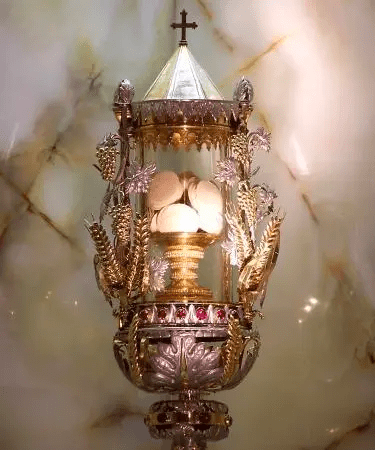

Blanot, France (1331)

In the Eucharistic miracle of Blanot (France, 1331), during the distribution of Holy Communion on Easter Sunday, a consecrated Host accidentally fell from a women’s mouth onto the cloth on her hands. As the priest tried to retrieve it, he saw that the Host had left a clear, round stain of blood on the linen. Shocked and moved, he showed the cloth to the people. The bishop of the diocese later had it carefully examined, and it was confirmed that the reddish mark resembled a true stain of blood from the consecrated Host.

The stained cloth was preserved as a relic and became an object of veneration. Despite the centuries that followed, including periods of turmoil like the French Revolution, the relic remained intact and was eventually sealed in a crystal tube with golden rings and placed in a special ostensorium. Even today, it is solemnly exposed to the faithful each Easter Monday in the parish church of Blanot, as a powerful reminder of Christ’s living presence in the Most Holy Eucharist.

Brussels, Belgium (1370)

In Brussels, an alleged desecration involved stabbing several consecrated Hosts, which responded by bleeding. The perpetrators were punished, and the unaffected Hosts were venerated as relics. The Church’s approval of this miracle reinforced the belief in the Eucharist’s resilience against sacrilege, and the event is still referenced in Belgian religious history.

Legnica, Poland (2013)

On Christmas Day 2013, during Mass at St. Hyacinth Church in Legnica, a Host fell to the floor and was placed in water to dissolve per Church protocol. Days later, a red substance appeared, which histopathological analysis by the University of Wrocław identified as human heart muscle tissue under severe stress, with type AB blood. In 2016, Bishop Zbigniew Kiernikowski permitted public veneration, declaring it a sign of Christ’s presence, though further Vatican review is ongoing.

Sokółka, Poland (2008)

At St. Anthony’s Church in Sokółka, a Host dropped during Communion was placed in water and later developed a red clot. Scientific examination by Dr. Stanisław Sulkowski revealed it to be living heart tissue, with bread fibers interwoven. Approved by the Archdiocese of Białystok in 2009, this miracle has been studied for its implications on the Eucharist’s living nature.

Buenos Aires, Argentina (1992-1996)

Under then-Archbishop Jorge Mario Bergoglio (later Pope Francis), three separate incidents occurred where Hosts turned into a reddish substance. In 1996, a Host from a church theft was found desecrated, later transforming into heart tissue, confirmed by Dr. Frederick Zugibe as human cardiac muscle with living cells. Bergoglio handled the cases with caution, and while local approval was granted, Vatican confirmation is still pending.

Tixtla, Mexico (2006)

During a retreat Mass in Tixtla, a Host began effusing a reddish substance in the presence of multiple witnesses. Dr. Ricardo Castañón Gómez’s analysis identified it as heart tissue, and the Diocese of Chilpancingo-Chilapa approved it in 2013. The miracle awaits final Vatican recognition

Vilakkannur, India (2013)

On November 15, 2013, at Christ the King Church in Vilakkannur, an image resembling Jesus’s face appeared on a consecrated Host during Mass. After a 12-year investigation involving theological and scientific scrutiny, the Vatican officially recognized it as a Eucharistic miracle in May 2025, with Apostolic Nuncio Archbishop Leopoldo Girelli set to proclaim it on May 31, 2025.

Investigative Process and Scientific Insights

Scientific studies of Eucharistic miracles have revealed striking findings. In cases like Lanciano (1971), Buenos Aires (1996), and Legnica (2013), the Host turned into human heart tissue, specifically myocardium. Professor Odoardo Linoli found Lanciano’s flesh was fresh cardiac tissue with no preservatives, despite 1,200 years. Dr. Frederick Zugibe confirmed living heart cells under stress in Buenos Aires. The University of Wrocław identified the same in Legnica. The blood, always type AB like the Shroud of Turin, showed no contamination or artificial manipulation.

These investigations uncovered unusual traits. In Sokółka (2008), Dr. Stanisław Sulkowski found living heart tissue mixed with bread fibers. No bacterial growth or mold appeared, even in water-soaked samples like Legnica. The blood in Lanciano and Santarém (1997) stayed stable for centuries. Dr. Ricardo Castañón Gómez noted white blood cells in Tixtla (2006), suggesting recent activity. Skeptics suggest hematidrosis or fungi, but the consistency across locations and Church vetting supports a miraculous interpretation.

The findings carry deep implications. Heart tissue under stress aligns with Christ’s suffering. The rare AB blood type adds mystery. Scientists analyze but don’t validate faith. The Church approves these for veneration, not as required belief, rooting the Eucharist in doctrine.

Conclusion

From Lanciano’s ancient transformation to Vilakkannur’s recent recognition, Eucharistic miracles reflect a continuum of divine signs across cultures and eras. Approved through rigorous investigation, they invite reflection on the Eucharist’s mystery, drawing millions to venerate these relics while respecting the primacy of faith over phenomena. For a complete list, resources like the Vatican International Exhibition of Eucharistic Miracles provide ongoing updates.